Main Second Level Navigation

- Welcome

- Why Toronto?

- History of the Department

- Vision & Strategic Priorities

- Our Leadership

- Our Support Staff

- Location & Contact

- Departmental Committees

- Department of Medicine Prizes & Awards

- Department of Medicine Resident Awards

- Department of Medicine: Self-Study Report (2013 - 2018)

- Department of Medicine: Self-Study Report (2018 - 2023)

- Communication Resources

- News

- Events

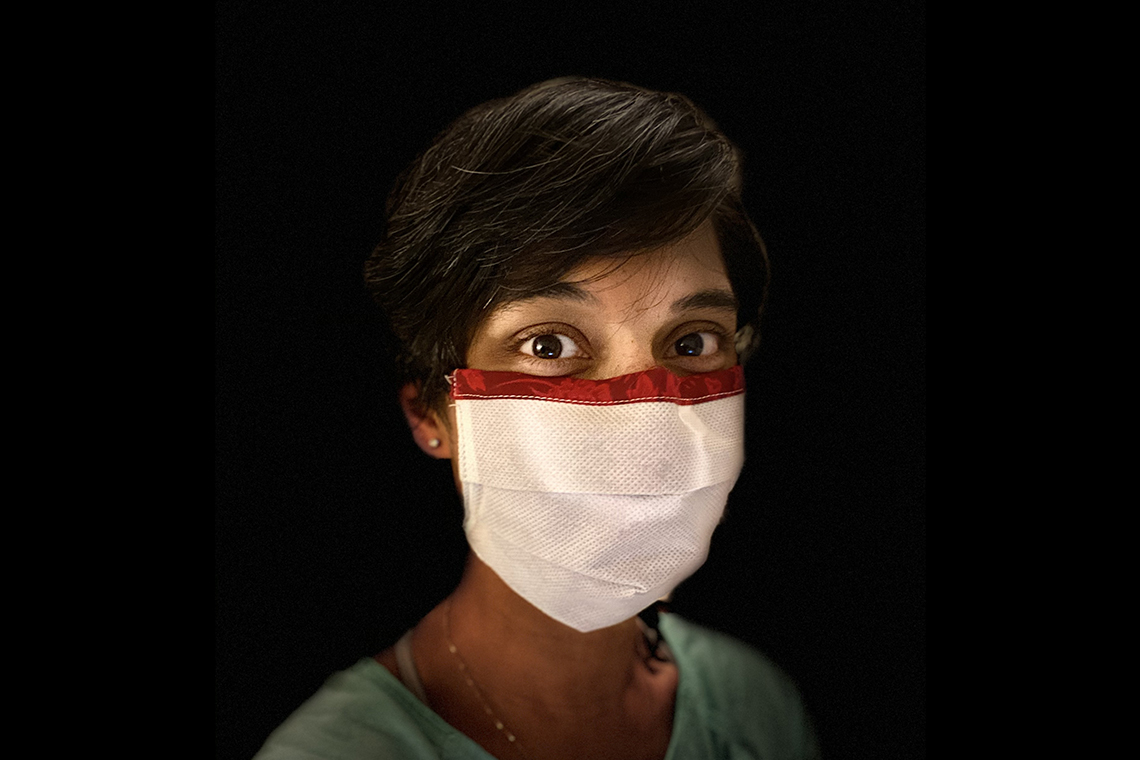

U of T researchers develop environmentally friendly surgical mask for front-line workers

Erin Howe

When COVID-19 emerged as a public health threat in early 2020, organizations representing health-care workers sounded the alarm about potential shortages of critical personal protective equipment (PPE).

When COVID-19 emerged as a public health threat in early 2020, organizations representing health-care workers sounded the alarm about potential shortages of critical personal protective equipment (PPE).

Now, two members of the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine are trying to find a sustainable way to ensure front-line workers who need PPE can always access it.

The initiative, dubbed the ROSE Project, is being led by Denyse Richardson, an associate professor in the department of medicine, and Reena Kilian, a lecturer in the department of family and community medicine – both in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

In an effort to develop a resuseable mask that meets Level 1 safety criteria, they’ve joined forces with a textile engineer, an architect, sewing experts, a knowledge translation expert and a medical student.

Richardson and Kilian recently spoke with Temerty Faculty of Medicine writer Erin Howe about the project and its progress to date.

What’s the significance of the initiative’s name?

Kilian: ROSE stands for Re-useable Open-Source Equipment.

Our plan is to develop a Level 1 face mask that people in health-care settings can wash and wear multiple times. The disposable, blue, pleated surgical masks you see are a good example of a Level 1 face mask. With our design, we hope to match the degree of protection those masks offer. And we want ours to feature materials that can be repeatedly cleaned and worn again.

Why did you undertake this project?

Kilian: Disposable surgical masks are only intended to be used once. They’re made of plastic and aren’t biodegradable or recyclable. We hope if there’s a reusable alternative developed, use of the disposable masks will fall so we can protect the planet while we protect each other and ourselves.

A lot of eco-friendly practices people had adopted before the pandemic stopped in the beginning of the pandemic over concern about spreading the virus – for example, people stopped using reusable bags at the store or travel mugs at the coffee shop. So, there’s a sense that we’ve really stepped back from the progress we’d made toward sustainability as a society.

The other issue has to do with supply and demand, which becomes less of a concern once there are reusable options. When we can re-wear a mask, you don’t need as many of them, which we hope can help lower the risk of a shortage like we saw in the spring.

Who inspired this work?

Kilian: We both work with patients who live in group homes and work closely with personal support workers. At the beginning of the pandemic, personal support workers had no PPE, which put patients who were already vulnerable at a disadvantage.

Richardson: Our idea came out of a desire to protect people who were lacking PPE when supply was low. We especially wanted to assist people working in shelters, long-term care homes and group homes. These people work with some of our most vulnerable populations and need to protect their clients and themselves.

Why is your design open source?

Kilian: We’ve all been affected by the pandemic and we want these efforts to benefit as many people as possible. There are already a few examples of other open-source PPE such as the Prusa face shield, which anyone with a 3D printer can make.

The idea is that if you’re someplace where you don’t have access to medical masks – either because there is a shortage or you’re in a remote area – this design will allow you to make a mask that you know will provide protection equal to what a standard surgical mask would.

For that reason, we have also focussed on using materials that are accessible to anyone.

What do you mean by “easily accessible” fabric?

Richardson: Our aim is to use materials someone could get no matter where they are. For example, one of our team members is looking at sheets from a discount retail chain with locations all over North America.

What’s the status of your work, and what do you hope will happen next?

Richardson: When we started this work, we thought it would be done in a few months. But it’s a complex process.

With the help of James Scott, a professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, we’re trying to define what and how materials can be used to create a mask that will satisfy important criteria, including filtration and proper fit while maintaining breathability.

In his aerosol lab, Scott has also been testing our masks against two standards – U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, also known as NIOSH, and American Society for Testing and Materials, better known as ASTM.

The next step is to find out how many times the masks can be re-used while maintaining their protective qualities. We’re hopeful that will happen in the year ahead.