Main Second Level Navigation

Apr 2, 2019

Retirement: Highlights of a new sunset

About Us, Cardiology, Clinical Immunology & Allergy, Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, Division of Dermatology, Education, Emergency Medicine, Endocrinology & Metabolism, Faculty, Gastroenterology & Hepatology, General Internal Medicine, Geriatric Medicine, Hematology, Infectious Diseases, Medical Oncology, Nephrology, Neurology, Occupational Medicine, Palliative Medicine, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Quality & Innovation, Research, Respirology, Rheumatology

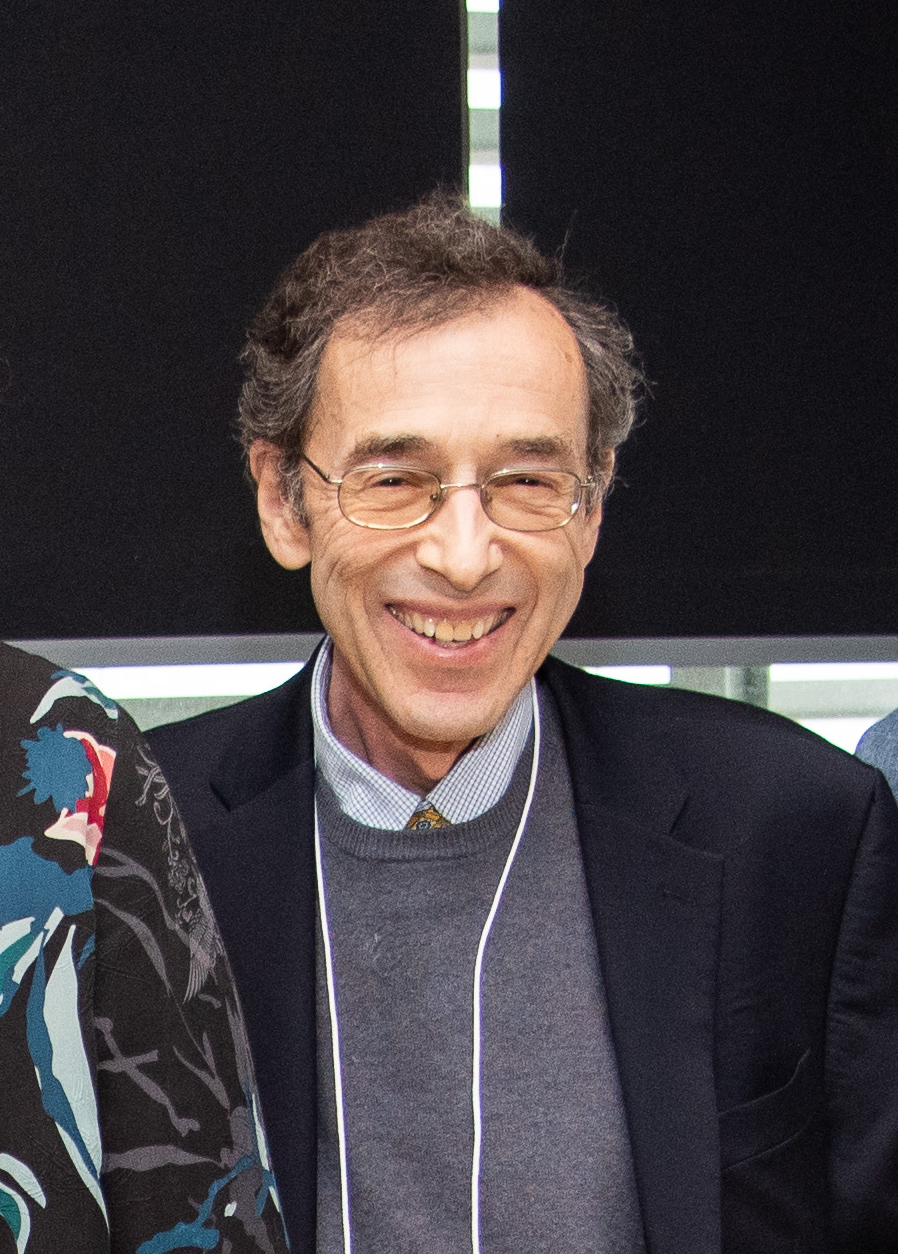

As the Department of Medicine prepares to launch a retirement toolkit to support late-career physicians, we are gathering stories and perspectives from faculty members who have retired from the DoM. University of Toronto Professor Emeritus George Fantus, now the Director Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism at McGill University Health Centre, shares stories of different approaches to retirement, from the physicians who never retired to those who did so enthusiastically, noting that there is no one rule for the approach to retirement.

As the Department of Medicine prepares to launch a retirement toolkit to support late-career physicians, we are gathering stories and perspectives from faculty members who have retired from the DoM. University of Toronto Professor Emeritus George Fantus, now the Director Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism at McGill University Health Centre, shares stories of different approaches to retirement, from the physicians who never retired to those who did so enthusiastically, noting that there is no one rule for the approach to retirement.